Stand still on a summer evening and you’ll hear it: a chorus of wings. To most of us, it’s just background noise, but hidden in those wingbeats is a stream of information about the health of our planet.

For decades, scientists have been ingenious in finding ways to study this hidden world, using nets, jars, and clever traps like the Malaise trap, which has been a trusted standard for insect surveys. These methods have taught us much of what we know about insect diversity.

At evolito, we asked a simple question: could we add another tool to the kit? One that listens to insects in real-time, without killing thousands of them.

Our insect sensor technology has been peer-reviewed and published in Scientific Reports, marking a significant breakthrough in biodiversity monitoring.

Turning wingbeats into data

Every insect in flight carries a unique signature. The rhythm of its wingbeat, the size of its body, even the tiny electric charges it picks up from the air, all leave faint traces that can be detected.

Our sensors capture those signals. By analysing them, we can measure insect abundance, activity, diversity, biomass, and even biodiversity uplift. It’s like tuning into nature’s quiet radio station, where each frequency tells the story of life on the move.

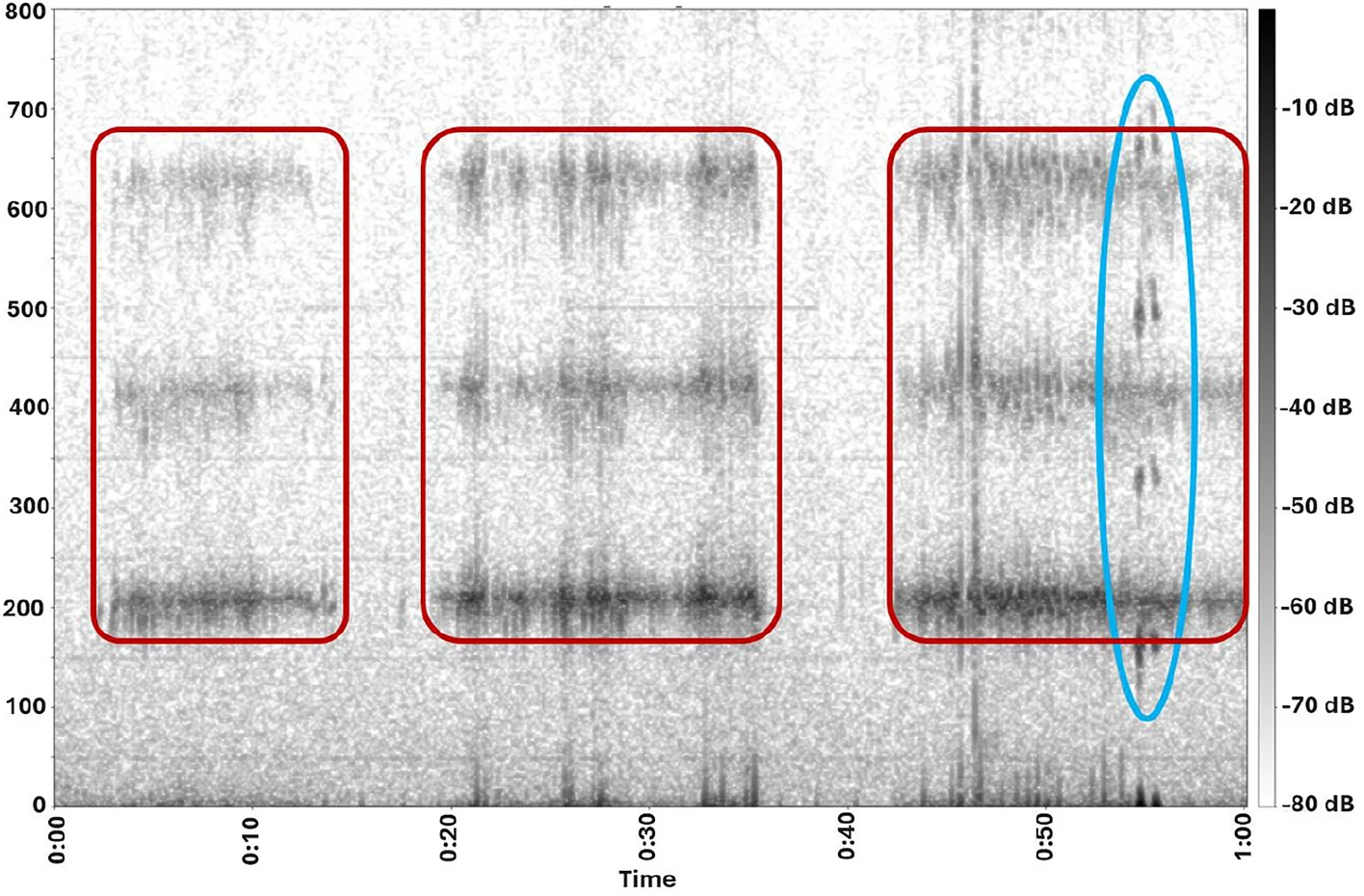

In the paper, you can see what insects look like when their wingbeats are turned into data.

Spectrogram of a 1-minute signal showing the activities of a bumblebee (Bombus spp., Apidae, Hymenoptera) (red) with a WBF (Wing Beat Frequency) of ≈ 210 Hz, and a fly (Brachycera, Diptera) (blue) with a WBF of ≈ 160 Hz.

In this example:

- The red boxes highlight the signal of a bumblebee (Bombus spp.) with a wingbeat frequency of about 210 Hz.

- The blue oval shows the signature of a fly (Brachycera, Diptera) with a wingbeat frequency of about 160 Hz.

Instead of nets or jars, we now get a live fingerprint of the insects passing by continuously and without harm.

Side by side with tradition

Scientific validation means putting our technology to the test against trusted methods. In this study, two of our sensors worked alongside two Malaise traps.

The results showed:

- Consistency: Two sensors produced more closely aligned results than two traps, highlighting the reliability of the signal-based approach.

- Comparable insect counts: Both methods captured similar trends in insect numbers.

- Biomass potential: Converting wingbeat signals into weight is complex, but promising. With more calibration, this will become increasingly accurate.

Why this matters

The study isn’t just about technology; it’s about opening new possibilities. With validated sensors, biodiversity monitoring can become:

Continuous: more like a live feed than a snapshot.

Non-invasive: capturing signals without capturing insects.

Scalable: deployable across many sites without needing to frequently visit the sites

For industries where biodiversity is now a material issue this creates a path toward richer, faster, and more accountable data.

Turning science into action

The value of this validation is not about replacing older methods, but about what becomes possible with continuous, non-invasive monitoring. With our sensors, biodiversity data can now be:

- Simple: our platform transforms the data into key metrics that help organizations to understand their impact on nature.

- Non-invasive: insects are measured without being captured.

- Actionable: data can directly support decision-making, reporting and stakeholder engagement.

For land managers, renewable developers, and restoration projects, this means decisions can be guided by living data, aligned with regulation, and grounded in ecological reality.

The takeaway

Every wingbeat is a data point. With evolito’s scientifically validated sensors, those signals can become the foundation for smarter conservation, better land management, and more resilient businesses.